Installation, The Margate School 2022-23

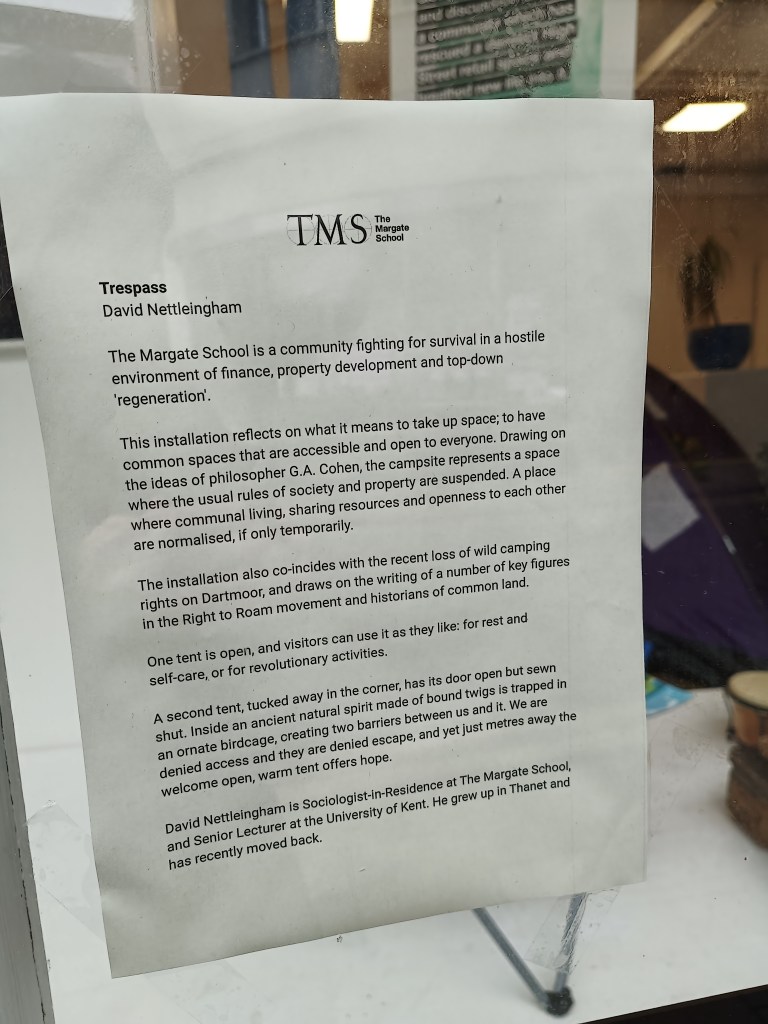

‘Trespass’ is an interactive installation and activity aimed at raising questions about access to land, enclosure and privatisation, ownership, and the role of trespassing in bringing ownership to light. A tent is set up – somewhere accessible but equally getting in the way of something – and over the course of days or weeks, a campsite is gradually expanded and developed around it. The site incorporates the imagery of a traditional camp, drawing on G.A. Cohen’s (2009) (not unproblematic but evocative) idea that a campsite represents a place where the usual rules of society and property are temporarily suspended, opening up opportunities for re-imagining relationships to both; where communal living, sharing resources and openness to others are normalised, albeit fleetingly.

As with all common land, the site is liable to disappear suddenly or be sold off to (imaginary) property developers.

Camp Diary

07/09/22

Pitching up and getting in the way

For my first intervention, I’ve decided to take up space and put myself in spaces that are more public and, frankly, annoying. I’ve been reading a lot on land ownership, space and the commons lately, so ‘common’ areas are my target: giving me a chance to be where other people are, to chat about common spaces, and to provoke reactions to there suddenly being something imposed in them.

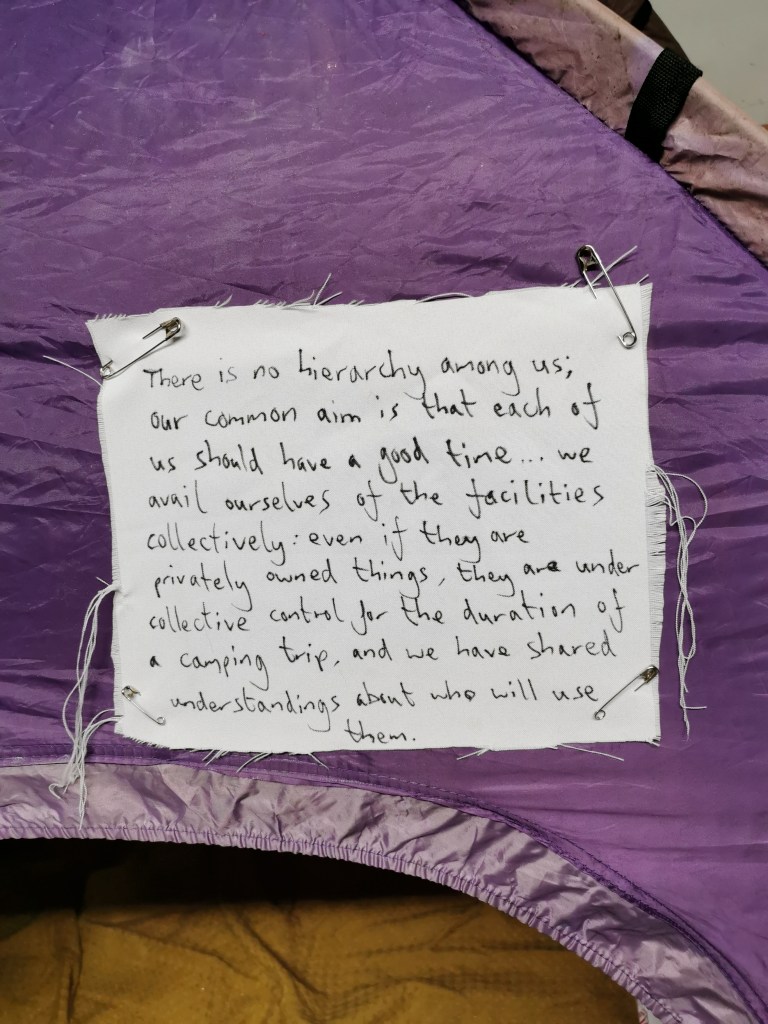

I remembered an essay I read about 10 years ago by the philosopher G.A. Cohen called Why Not Socialism? In it he looks to a camping trip as an ideal breeding ground for ideas on living in socially-transformative ways; as a scenario in which dialogue is more open; ownership of things and spaces are shared.

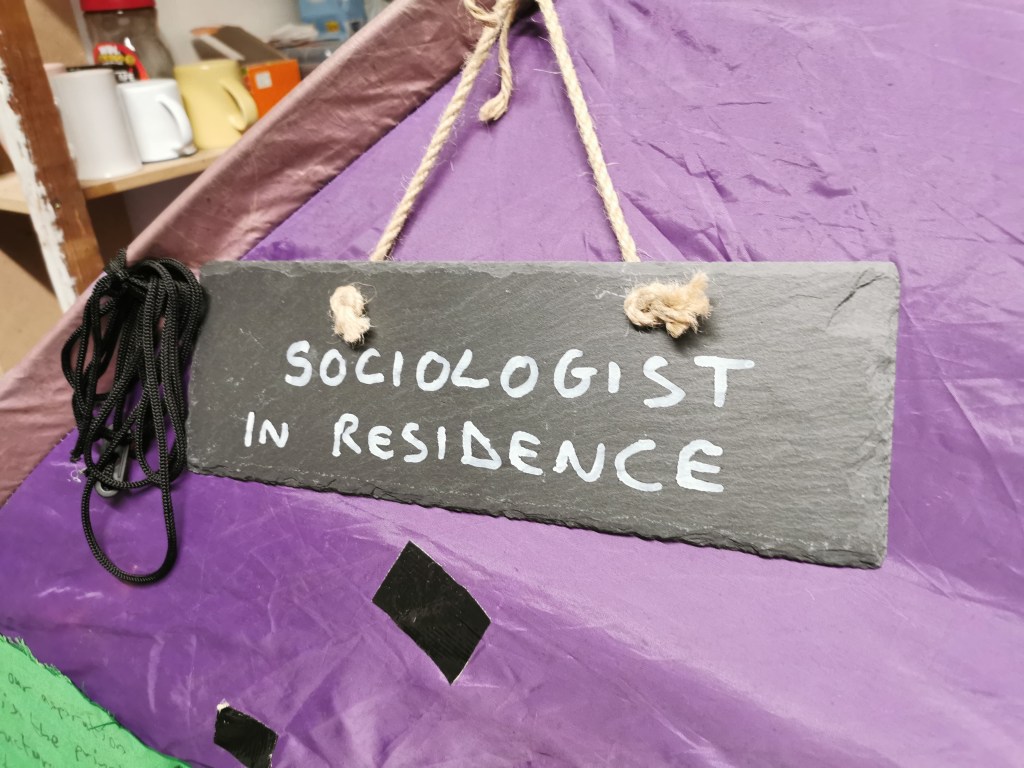

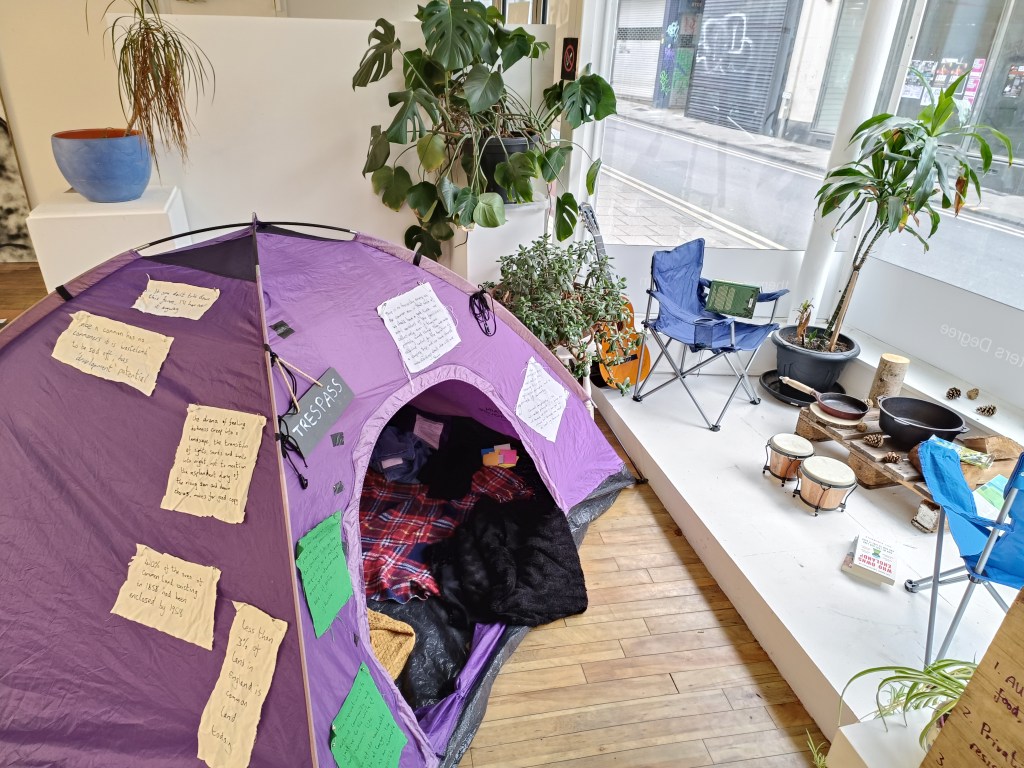

I wasn’t and still am not entirely convinced by the thesis as a means to the ends Cohen was looking for, but I like a lot of the ideas (and camping), and it did make me think of a way I could intervene. I removed all the furniture from the postgraduate kitchen space on the top floor of the building, replaced it with camp chairs, a pile of firewood, a washing line, cooking pots for the leaky roof, and set up a tent. Quotes from the book are pinned to the outside, and inside there are blankets, maps, books, pens and paper. I made some wooden signposts to put around the building to guide people to the ‘Common Ground Campsite’ (a phrase I have borrowed from my work with the Woodcraft Folk). The MA students now cannot avoid it, but hopefully will also use it for whatever they want. I’ve begun to put up sheets of paper with prompts and questions hanging with the socks on the washing line as a way to start thinking through some things I hope to develop.

The campsite can be moved to another part of the building easily at any point or just disappear completely – a risk that all common spaces face. Does an imposition like this privatise the space and make it inaccessible even while it proclaims to be a way of facilitating discussion and belonging? Have I altered the access rights to the kitchen as a useful, functioning part of the top floor? Am I making a point about the precarity and fragility of the commons? Will anyone talk to the guy sat in a makeshift campsite looking a bit to eager to ask them questions? I have a lot of things to work out.

24/11/22

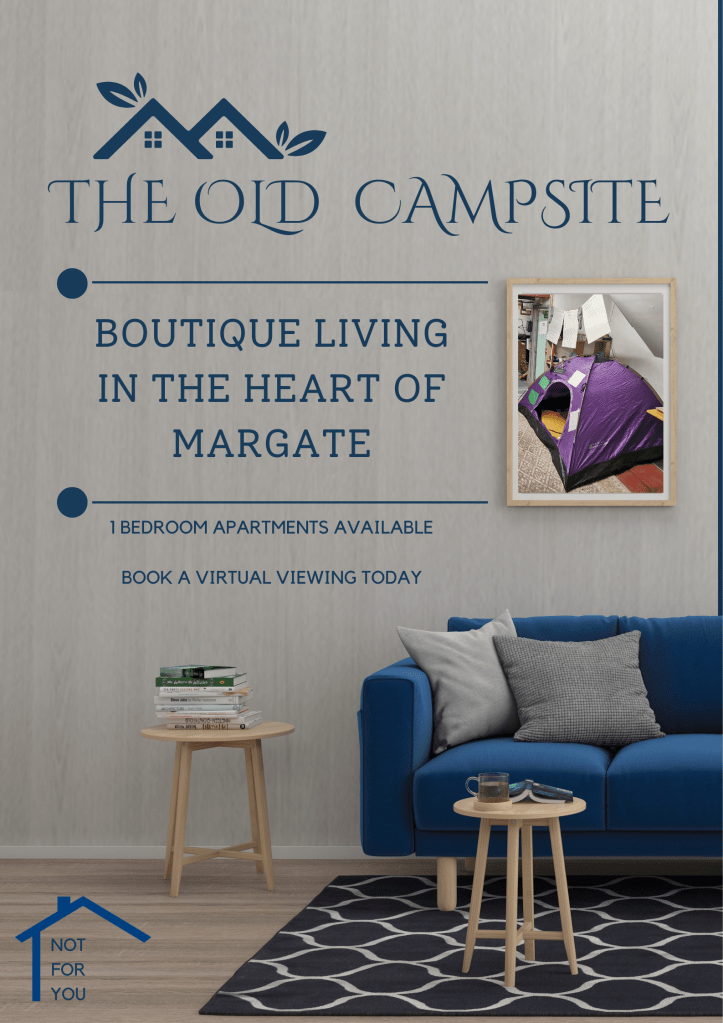

From common ground to 27 one-bed flats

Today I removed my campsite from the postgraduate kitchen – its time there has come to a natural end I think. The tent will reappear somewhere else soon for a new purpose.

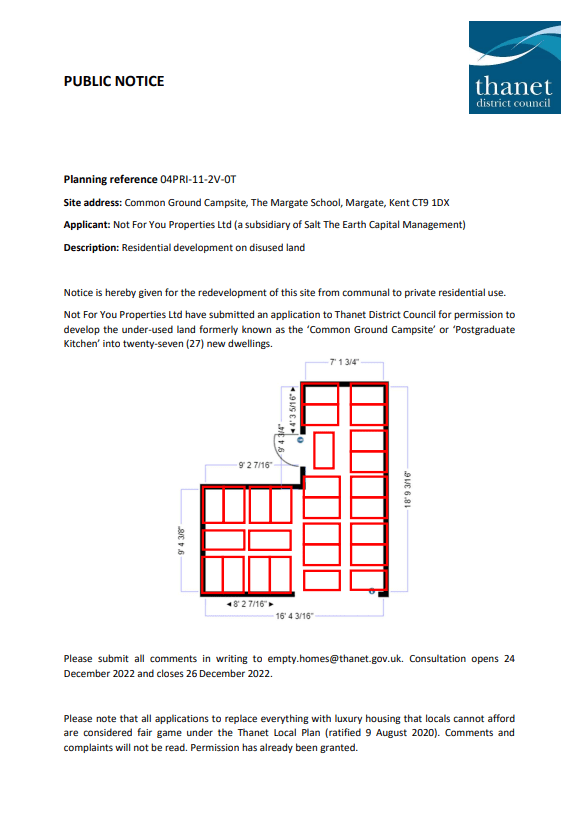

One of the themes of the campsite was ‘common ground’ – thinking about communally used spaces and their potential, so I thought it would be fitting to end my occupation realistically: with the sell-off of the space to (imaginary) property developers.

Not For You Properties Ltd (a subsidiary of Salt The Earth Capital Management) have purchased the site and are planning to redevelop the postgraduate kitchen into 27 one-bed luxury apartments. A ‘consultation’ will be held, but the decision is already made.

23/01/23

Trespass installation in the gallery

I am taking up space once again – occupying space. My campsite has re-emerged after its tragic loss to (pretend) developers back in November.

This time I am camping in the main gallery, on full public display. The message the tent is trying to get across has evolved, incorporating quotes from Marion Shoard’s (2000) This Land is Our Land and Nick Hayes’ (2022) The Trespassers’ Companion, as well as drawing on the sentiments of the Right to Roam movement and the pressing campaign to reinstate wild camping on Dartmoor.

The installation is aimed at raising questions about access to land, enclosure, ownership, and the role of trespassing in bringing ownership to light. It builds on my previous campsite’s focus on how easily common land is taken from people under a regime of unregulated and hostile capitalistic models of control, and the need to constantly fight for what we have.

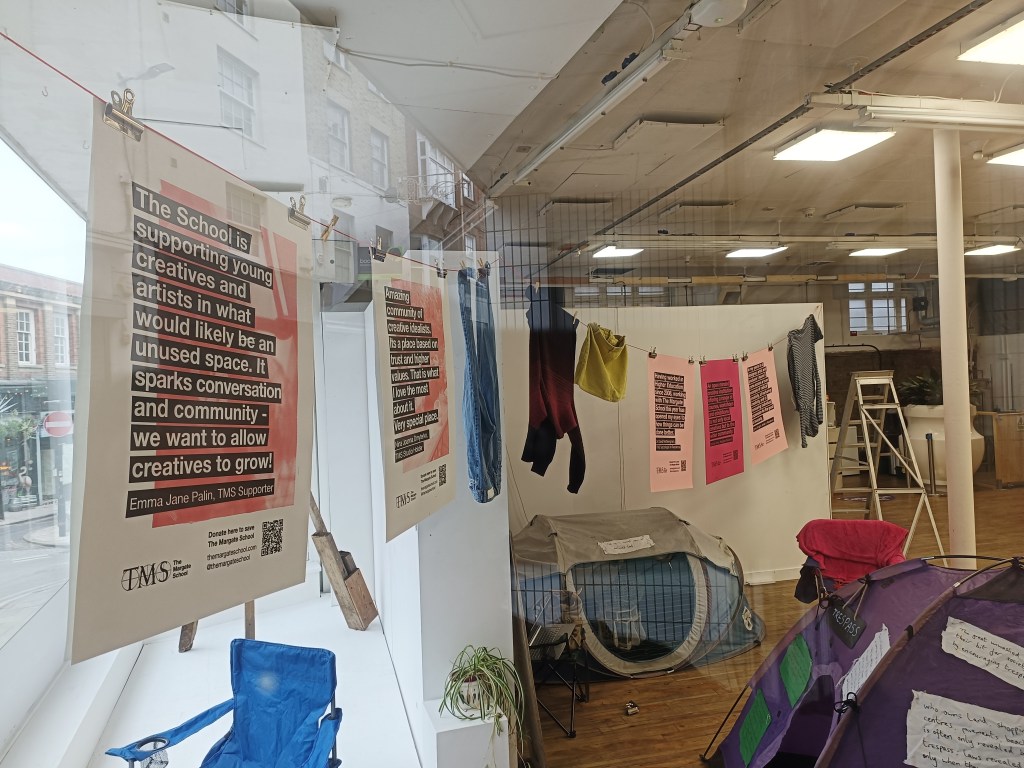

It is also an (albeit abstract) engagement with the fate of The Margate School itself – where ownership, capital threatening community, and the liability of common or alternative spaces to disappear or be crushed are all present concerns.

In one open tent, people are encouraged to trespass and use the space. The campsite rules state that must only be used for 1. dreaming of a better world, 2. self-care, 3. building relationships or 4. revolutionary activities. It is full of books and blankets, and warm compared to the freezing temperatures of the School’s building. Hanging above the campsite is a washing line with posters for the Save the Margate School campaign, and… washing.

A second tent, tucked away in the corner, has it’s door open but sewn shut. Inside a person/poppet/some ancient natural spirit made of bound twigs is trapped in an ornate birdcage, creating two barriers between us and it. We are denied access and they are denied escape, and yet just metres away the welcome open, warm tent offers hope.